Introduction

Additional mutations at chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) diagnosis have been shown to variably affect tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) response and were inconstantly detected at loss of response. Contradictory observations may have resulted from difficulties in reliably inferring CML clonal architecture from mutations quantified by NGS, BCR::ABL1 by qRT-PCR, ABL1-TK by RNA-Seq. The RESIDIAG study was designed to identify at diagnosis molecular markers predictive of TKI treatment failure and analyze the clonal dynamics using asymmetric capture sequencing (aCAP-Seq).

Methods

DNA samples from 60 TKI responders (median follow-up: 7.1 years) were sequenced at diagnosis by aCAP-Seq, allowing quantification and breakpoint sequencing of genomic BCR::ABL1 fusion together with 43 myeloid genes, including ABL1 with a limit of detection of ~0.1% for BCR::ABL1 and 0.5-1% for SNVs and Indels. In parallel, CML patients who experienced treatment failure (ELN 2020) were sequentially analyzed at diagnosis and at failure (n=53), at diagnosis only (n=1), and at failure only (n=3). Small deletions and BCR::ABL1 breakpoints were analyzed to search for microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ) repair signatures. Mutation analysis followed strict medical standards.

Results

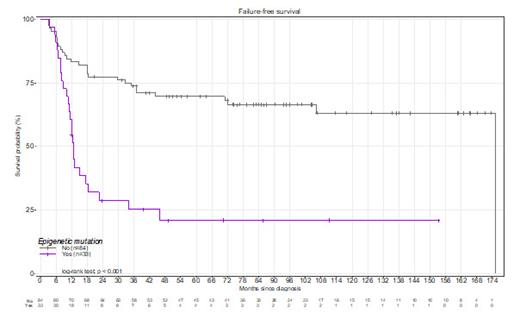

The proportion of patients receiving imatinib at diagnosis wasn't statistically different (p=0.08; Pearson's Chi-square test) between responders (70%) and the failure group (56%). At diagnosis, the number of mutations was higher (p<0.001, t-test with Welch correction) in the failure group (0.9±0.1) as compared with responders (0.18± 0.05). ASXL1, DNMT3A, and TET2 were more frequently mutated at diagnosis in the failure group (38.6%, p<0.001; 10.5%, p=0.01, and 4.3%, p=0.025 respectively; Pearson's Chi²test) as compared with responders (6.7%, 0% and 0% respectively) and the presence of a mutation in one of these genes was highly associated with a reduced failure-free survival (p<0.001, Log-ranked test, Figure 1). An MMEJ signature at BCR::ABL1 breakpoints was more frequent (p=0.014, Pearson's Chi² test) in the failure group (29.1%) than in the responder group (9.1%). and was significantly associated with the ELTS score (p=0.005, Pearson's Chi² test) but not the Sokal score (p=0.017, Pearson's Chi² test). At first failure, 69% of patients had additional mutations in ASXL1 (39%), ABL1-TK (38%), DNMT3A (18%), or TET2 (15%), while other genes were rarely (<5%) mutated. ASXL1 mutations found at diagnosis were still detectable in 18/22 patients at failure and VAF suggested that double mutant BCR::ABL1/ ASXL1 clones were driving TKI failure with or without BCR:: ABL1 tyrosine kinase domain mutation (TKD). ASXL1 mutations disappearing upon treatment were mostly at low frequency <5% at diagnosis and thus possibly not clonally related to CML. Furthermore, a stepwise selection of variables followed by multivariate analysis with the Fine-Gray model identified the age of patients (sdHR [95% C.I.] = 0.99 [0.97-1.00]; p=0.08) and the presence of a mutation in epigenetics regulators at diagnosis as factors affecting the onset of TKD mutations (sdHR = 3.01 [1.76-5.15]; p<0.001). Intriguingly, co-occurring mutations in DNMT3A and TET2 were found in five patients at TKI failure. Their allelic frequency kinetics suggested that these belonged to the same clone driving CML relapse in 4/5 CML patients, while one patient also had a TKD mutation likely involved in CML relapse. Finally, multivariate COX regression analysis identified two independent predictors of TKI failure at diagnosis: a high-risk ELTS score (p=0.001; hazard ratio=3.42 [1.62-7.22] with low-risk as baseline) and a mutation in ASXL1, DNMT3A or TET2 (p=0.002; hazard ratio=2.87 [1.49-5.51]).

Conclusion

Altogether these results strongly point to the contribution of epigenetic regulator mutations in the emergence of TKI failure in CML and warrant further biological studies to better understand the underlying mechanisms

Disclosures

Dulucq:Novartis, Incyte Biosciences: Honoraria, Speakers Bureau. Wagner-Ballon:Novartis: Honoraria; Alexion: Consultancy, Honoraria. Nicolini:Pfizer: Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; SUN pharma: Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; INCYTE BIOSCIENCES: Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Novartis: Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding, Speakers Bureau; BMS: Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees. Roy:Novartis: Honoraria, Research Funding, Speakers Bureau; Pfizer: Honoraria; BMS: Honoraria, Research Funding; Incyte biosciences: Honoraria. Etienne:Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research Funding; BMS: Honoraria; Pfizer: Honoraria; Incyte biosciences: Honoraria. Rea:Pfizer: Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Speakers Bureau; INCYTE BIOSCIENCES: Consultancy, Honoraria, Speakers Bureau; Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Speakers Bureau. Sloma:Novartis: Honoraria, Speakers Bureau; Incyte Biosciences: Honoraria, Speakers Bureau; Agilent Technologies: Patents & Royalties.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal